Supporters of a people’s initiative to ban face coverings in public have carried the vote with a small majority of 51.2%.

A decade after another national vote – brought by the same committee – which banned the building of minarets, Switzerland will now introduce a clause in its constitution to outlaw face coverings, including the Islamic burka and niqab, in public spaces.

In doing so, it will join five other European countries, including neighbours France and Austria, who have already banned such garments in public.

Exceptions to the law will include face coverings for reasons of security, climate, or health – which means the current protective masks worn against Covid-19 are acceptable. Niqabs and burkas will still be allowed in places of worship.

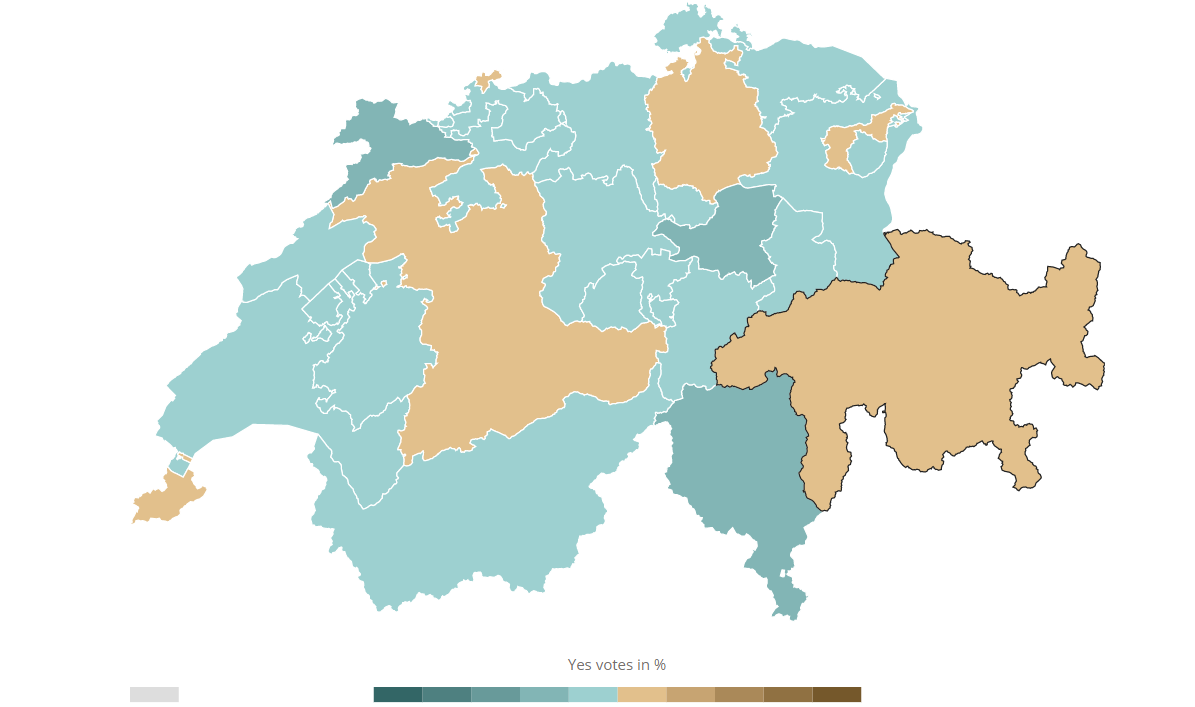

Final results on Sunday showed just six of the country’s 26 cantons rejecting the initiative, which was launched in 2016 by a right-wing committee. Turnout was just over 50%, a little above average for the country.

It’s only the 23rd time in 130 years that a people’s initiative has been accepted, and the first time since 2014. Swiss citizens have voted on a total of 219 such initiatives – launched by gathering 100,000 signatures – over the course of the country’s modern history.

It also marks a defeat for the government and parliament, who opposed the ban on the grounds that it was unnecessary – both because of the low number of niqab-wearers in the country, and because they said the 26 cantons can legislate on such issues themselves.

Opponents had also attacked the burka ban as being a case of anti-Islam “symbolic politics” which didn’t tackle any real problem. Only a few dozen women wear such veils in Switzerland, they claimed. Yet with some of the discussions, “you’d almost think we live in Kabul”, Justice Minister Karen Keller-Sutter had said during the campaign.

On Sunday, Walter Wobmann of the right-wing People’s Party, who led the initiative campaign, said the vote was not just symbolism. “Facial coverings are contrary to our value system,” Wobmann told Swiss public television, SRF. He said there were now clear rules in place so that “people know that in our country, you show your face in public”.

Wobmann’s party colleague Jean-Luc Addor said the initiative succeeded because it managed to build support beyond merely right-wing camps: on Sunday he praised the involvement of left-wing feminists and of progressive Muslims, some of whom also supported the ban.

Addor said that “some Muslims understood that the niqab is a clear symbol of radical Islam”, which represents not only a challenge for “our civilisation” but also for Muslims themselves.

Saida Keller-Messahli, founder of the Forum for a Progressive Islam and a prominent backer of the ban, said the result was a rejection of a “totalitarian ideology which has no place in a democracy”. She added that she thinks the result will be “understood” abroad.

Other Muslims and Muslim groups were not so upbeat. The Islamic Central Council of Switzerland (ICCS) said the result was a “big disappointment for all Muslims who were born in and grew up in Switzerland”. Ferah Ulucay, secretary-general of the ICCS, said the vote “had succeeded in anchoring in the constitution a widespread islamophobia in Switzerland”.

Pascal Gemperli of the Federation of Islamic Organisations in Switzerland said the vote “targeted a specific community, just like with the minarets [in 2009]”. He said it wasn’t clear what would happen next, but that he had some fears for the security of Muslims in the country.

Feminist groups had also been heavily involved in the campaign, with some seeing the face coverings as a symbol of patriarchal oppression, while others opposed the ban on the grounds that women should be allowed dress how they like.

Reacting on Sunday, Tamara Funiciello, a well-known feminist from the left-wing Social Democrats, said the result would have no impact on real problems like sexism, racism and violence. It’s another example of women being told what they can and can’t wear, she said.

Memory of minarets

Switzerland, like many other western European countries, has debated over the past decades how best to integrate its Muslim community, who are estimated to make up about 5% of the total population.

In November 2009, 57.5% of voters accepted another people’s initiative – proposed by the same committee behind the burka vote – to ban the building of minarets in the country: a result that went against the predictions of opinion polls and which came as a shock to the political establishment.

Debates about the various symbols of Islam, including burkas and niqabs, which were part of the discussion at the time, continued in the years after, and two cantons introduced full face-covering bans in the past decade – St Gallen and Ticino. Other cantons have previously rejected such proposals.

In the southern region of Ticino, where over 60% of the population backed a ban in 2016, the first three-and-a-half years after it came into force saw 60 people being charged for infringements – 32 of them sport hooligans, and 28 women wearing facial coverings.

Over half of all Swiss cantons already have regulations in place that ban the wearing of face-coverings during demonstrations or sports events.

Falling support

Public support for the ban was found to be high in opinion polls early on in the campaign, with some reporting over 60% of respondents in favour.

After that, the advantage faded somewhat, and the final poll by the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation, two weeks before the vote, reckoned that 49% planned to vote “yes” and 47% “no”; only a small number of voters had said they were still undecided.